Regression Analysis > Reverse Causality

What is Reverse Causality?

Reverse causality means that X and Y are associated, but not in the way you would expect. Instead of X causing a change in Y, it is really the other way around: Y is causing changes in X. In epidemiology, it’s when the exposure-disease process is reversed; In other words, the exposure causes the risk factor. For example,

“…one may be tempted to say that low social status causes schizophrenia, [but] another plausible explanation is that schizophrenia causes downward social mobility…” ~ Gerstman**

Due to the fact that Y unexpectedly comes before X, reverse causality bias is sometimes called the “cart before the horse bias.”

According to Katz (2006), identifying reverse causality is sometimes a matter of “common sense.” For example, a study might find that brown spots on the skin and sunbathing are linked. While it is plausible that sunbathing can cause brown skin spots, it’s highly unlikely that the brown spots cause sunbathing. On the other hand, a study may find that smoking and depression are linked. It could be that smoking causes depression, or it could be the other way around. The likelihood is that they both cause each other (smoking → depression and depression → smoking) perhaps because smokers feel societal pressure to quit, but may not have the willpower to do so. When this symbiotic relationship happens, it’s called simultaneity.

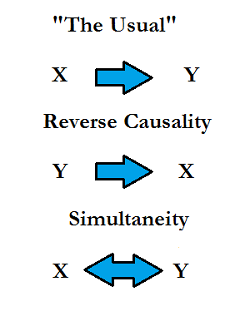

Reverse Causality vs. Simultaneity

The two terms are similar, but they are not the same. Their definitions are so close, they are often confused:

Simultaneity: X causes changes in Y and Y causes changes in X,

Reverse Causality: Y causes changes in X.

**Interestingly (and perhaps surprisingly), there are some studies which show schizophrenia is more common in lower-income neighborhoods. See Werner et. al. Socioeconomic Status at Birth Is Associated With Risk of Schizophrenia: Population-Based Multilevel Study.

References:

Gerstman, B.(2003). Epidemiology Kept Simple: An Introduction to Classic and Modern Epidemiology, Second Edition.

Katz, M. (2006). Study Design and Statistical Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians.

Wanburg, C. (Ed.) (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization.