Design of Experiments > The Hawthorne Effect

Contents (click to skip to that section):

- Hawthorne Effect Definition.

- History of the Hawthorne Effect.

- Is the Hawthorne Effect Real?

- Placebos, Pygmalion, and Other Self Fulfilling Prophecies.

Watch the video for a summary of the Hawthorne effect:

Hawthorne Effect Definition

The Hawthorne Effect, also called the Observer Effect, is where people in studies change their behavior because they are watched. A series of studies in the 1920s first shone light on the phenomenon after researchers investigated how several conditions (i.e. lighting and breaks) affected worker’s output. Output went up up during the studies; It returned to normal after the research team left. This led to a whole era of research that attempted to control for the effect an observer can have on an experiment.

Some people say the “Hawthorne Effect” wasn’t real and output didn’t rise to any real level. There haven’t been any experiments since then that have duplicated the findings. However, the term “Hawthorne Effect” persists–even in textbooks. It is now used to describe any situation where there is a short-term increase in output.

Back to Top

History of the Hawthorne Effect

The major finding was that no matter what change the workers were exposed to, output improved. But, production went back to normal at the end of the study. This suggested watched employees worked harder.

Who Came Up With The Term?

Although the experiments took place in 1924-1932, the term Hawthorne Effect wasn’t used until much later. There is debate about who actually came up with the term. Some people think it was first used in the 1950s by Henry A. Landsberger during his analysis of the Western Electric experiments. See here and here. Others think that it was possibly coined by John French in 1953. See here and here.*

Back to Top

Details About The Experiments

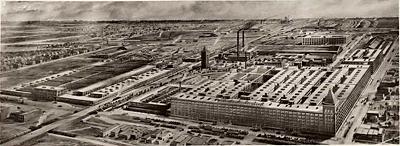

The Hawthorne telephone factory experiments took place over several years. Illumination studies. Researchers from the National Academy of Science played around with lighting levels, took place sporadically during a two and a half year period from 1924 to 1927. (Note: if you want to get an idea of what the factory conditions looked like, check out this AT&T archive video. The Hawthorne experiment starts at about 7:10).

The Hawthorne telephone factory experiments took place over several years. Illumination studies. Researchers from the National Academy of Science played around with lighting levels, took place sporadically during a two and a half year period from 1924 to 1927. (Note: if you want to get an idea of what the factory conditions looked like, check out this AT&T archive video. The Hawthorne experiment starts at about 7:10).

List of Changes

These experiments were conducted on entire departments (from Roethlisberger & Dickson):

- 1a: experimental groups from three departments showed output increases. These continued even when lighting levels were decreased.

- 1b: one experimental group worked with increasing lighting levels. One control group worked with constant lighting levels. Both groups’ output showed a small, but significant, increase.

- 1c: Similar to 1b, except the experimental group worked under decreasing lighting levels. Output increased for both groups until the lighting levels in the experimental group went too low (1.4 foot candles) to see properly.

- 1d: only involved two women. The researcher told the women that bright lighting was better and pretended to replace bulbs with better ones. The women stated they preferred the “better” light. The women’s belief about “good” lighting levels affected them more than what the actual lighting levels were.

According to Blalock and Blalock (1982, p. 72), to the surprise of the researchers:

“…each time a change was made, worker productivity increased…..As a final check, the experimenters returned to the original unfavorable conditions of poor lighting….Seemingly perversely, productivity continued to rise.”

End of The First Experiment

The National Academy called off the experiment as it proved nothing. However, Western Electric decided to undertake further studies. Harvard University then became connected with the new studies. Sociologist Elton Mayo supervised most of them.

Experiment, Part 2

In another Hawthorn study, 14 telephone assemblers took part. After they were moved to a test room to work, there was no increase in output (i.e. there was no Hawthorne effect). However, the researchers did note that the people in the study kept up with group expectations of what they thought was good output for the day. Team members were labeled “speed kings” or “slaves.” If output was too high in the morning they tended to slow down to meet expectations.

The Great Depression

The experiments continued until 1932, when the workers in the experiment were laid off during the Great Depression. a report was actually never published, despite the notoriety of the Lighting experiment. The data from the experiment was considered “lost” until recently. Steven Levitt and John List from the National Bureau of Economic Research found the data in two library archives.

An interesting (bit probably irrelevant) note: Theresa Zajac was one of the original experiment participants. She still worked at the same plant when Western Electric held their 50th anniversary celebration.

Back to Top

Is the Hawthorne Effect Real?

Henry McIlvaine “Mac” Parsons was one of the first people to uncover some real problems with the Hawthorne experiment’s results. In 1970 he studied second-hand and first-hand accounts of the research, finding some serious problems. These included factors that were completely ignored:

- The test room was much smaller and quieter than the main floor. The room also had better air flow and lighting.

- Supervisors were friendly and tolerant when the researchers were around. This may have affected performance.

- The testing room had a friendlier atmosphere than the main floor. Workers talked between themselves more.

- Two women were replaced mid-way through the experiment for being too slow. One of the replacements was so enthusiastic, she became the group leader.

Perhaps the two most important factors that weren’t accounted for were also ignored by the researchers. When the workers were on the main floor, they earned a base rate plus a bonus; The whole department’s performance determined the bonus. Five workers output in the test room determined how much extra those workers received, so one person’s output could have a major effect on the team’s paycheck. This meant that team members would be more motivated to ramp-up output. This motivational effect is well-known in behavioral science today, but back in the 1920s/1930s it had not been developed yet.

The Myth Continues

Parsons made his findings well-known, but many authors of current textbooks continue to include the Hawthorne Effect without question. When asked why he thought people persisted in spreading the myth despite his well-publicized findings, Parson’s replied, “They’re lazy.”

In a NY Times article from 1998, psychology professor Dr. Richard Nisbette from the University of Michigan called the Hawthorne effect “a glorified anecdote,” partly due to the tiny sample of workers studied. The New York Times article itself was titled “Scientific Myths That Are Too Good to Die.”

A Closer Look

A closer look by a group of University of Chicago researchers suggests that there may never have been a “Hawthorne Effect” in the first place. After analyzing the original data, Levitt and List came to the following conclusion:

” Our analysis of the newly found data reveals little evidence to support the existence of a Hawthorne effect as commonly described; i.e., there is no systematic evidence that productivity jumped whenever changes in lighting occurred.”

The output seen in the original study could have been due to factors other than observation. Recent analysis of the tests highlight the simple fact that the Great Depression loomed. That alone may have had an effect on workers. The general opinion seems to be that if the Hawthorne effect exists, it exists in ways that aren’t really understood. This may have a huge impact on future studies.

The research that came out of the study influenced a generation of researchers. The field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology grew out of the Hawthorne studies.

“In the history of science, certain contributions stand out as signal events in the sense that they influence a great deal of what follows. The Hawthorne Experiments exemplify this phenomenon in the field of industrial work and have been the subject of serious subsequent commentary and reanalysis.” (Bloombaum, 1983)

Self Fulfilling Prophecies

The Hawthorne Effect remains as a way to describe the increase in output seen in similar studies. These changes are sometimes called Self-Fulfilling Prophecies. When a researcher sets up an experiment, they are hoping that their hypothesis is correct. Otherwise, the experiment would fail. These hoped-for changes mean it is more likely a researcher will accept, rather than reject, their hypothesis statement.

The Hawthorne Effect isn’t the only effect of expectation. The Placebo Effect and Pygmalion Effect can also affect the results of an experiment.

The Hawthorne Effect isn’t the only effect of expectation. The Placebo Effect and Pygmalion Effect can also affect the results of an experiment.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

In the placebo effect, any medical intervention results in a positive outcome. That’s even if a patient receives a sugar pill instead of a “real” pill. Modern research is showing links between changes in brain chemistry and placebos. The placebo effect is even seen in patients told that they are taking placebos. The placebo effect has even been shown to lower cholesterol, as this study shows.

The Pygmalion effect is where higher expectations lead to better results. With this self-fulfilling prophecy, people internalize positive labels. Those people with positive labels succeed. The opposite of the Pygmalion effect is the Golem effect. People internalize negative labels and fail. Studies in controlled settings have been hard to come by.

2. If you have 30 minutes, I highly recommend this BBC Radio program. It dissects the Hawthorne Effect and explores the history. It also features several experts in the field such as:

- The Hawthorne Museum in Cicero.

- The Baker Library archive.

- Professor Michel Anteby at Harvard Business School.

- Professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld of Yale Business School. He met the original participants in the study back in the 1970s.

- Mecca Chiesa of the University of Kent.

References:

Blalock, A. & Blalock Jr., H.M. (1982). Intro to social research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Prentice-Hall.

Bloombaum, M. (1983). The Hawthorne experiments. A critique and reanalysis. Sociological Perspectives. January, 26(1), 71-88.

Landsberger, Henry A. Hawthorne Revisited, Ithaca, 1958.

Levvit, S & List, J. Was There Really a Hawthorne Effect?. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3 (1): 224–238. Retrieved 12-20-2015 from http://www.nber.org/papers/w15016.pdf.

Mayo, Elton. Hawthorne and the Western Electric Company. Routledge, 1949.

McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P; Warner; Iliffe; Van Haselen; Griffin; Fisher (2007). “The Hawthorne Effect”. BMC Med Res Methodol 7: 30.

Rice, Berkeley. The Hawthorne Effect: Persistance of a Flawed Theory. Retrieved 12/20/2015 from https://www.cs.unc.edu/~stotts/204/nohawth.html.

Roethlisberger,F.J. & Dickson,W.J. (1939) Management and the Worker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.